n o w h e r e is a Mod of the game Unreal Tournament 2003. UT is a multiplayer first-person shooter game. There’s a sketchy plot about a victorious invasion of “human space” by an armada of alien warships, and the establishment of gladiatorial tournaments for the entertainment of the subjugated masses. Players compete in teams against aliens, gene-boosted humans, and robots. The goal is to get yourself a bad-ass weapon, like the Lightning Gun, and seek to achieve maximum mayhem.

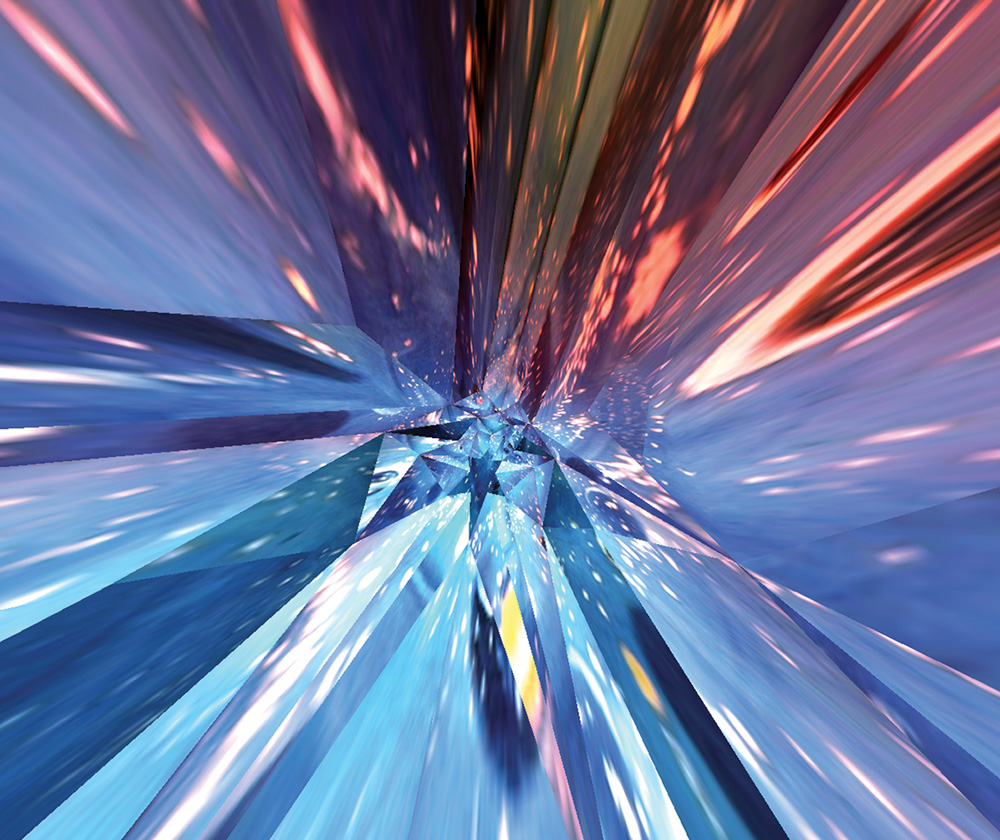

UT In the hands of Sylvia Eckermann, however, UT is something entirely different. She has stripped out all of the details of the original UT world and left only the rough geometrical shapes and planes of the virtual space. What remains is a surprisingly serene world of soft lighting and almost transparent surfaces. And unlike the original UT, there is no strategy or competitive climax, no discreet beginning or end, no explicit narrative. There is no obvious point to the experience, except to calmly float through a minimalistic cosmic universe.The transformation that Eckermann has accomplished is startling and ironic. Who would have ever thought that lurking beneath the surface of a world explicitly built for slaughter was a parallel world with an opposite soul?

This yin/yang polarity seems to be exactly Eckermann‘s intent; a ritual healing by appropriation, a gentle revenge. Through a process of subtraction, stripping away detail and reverse engineering the game engine, Eckermann’s virtual world becomes more abstract yet oddly more human. n o w h e r e is an act of pacifist reappropriation, with Eckermann playing the part of humanistic saboteur.

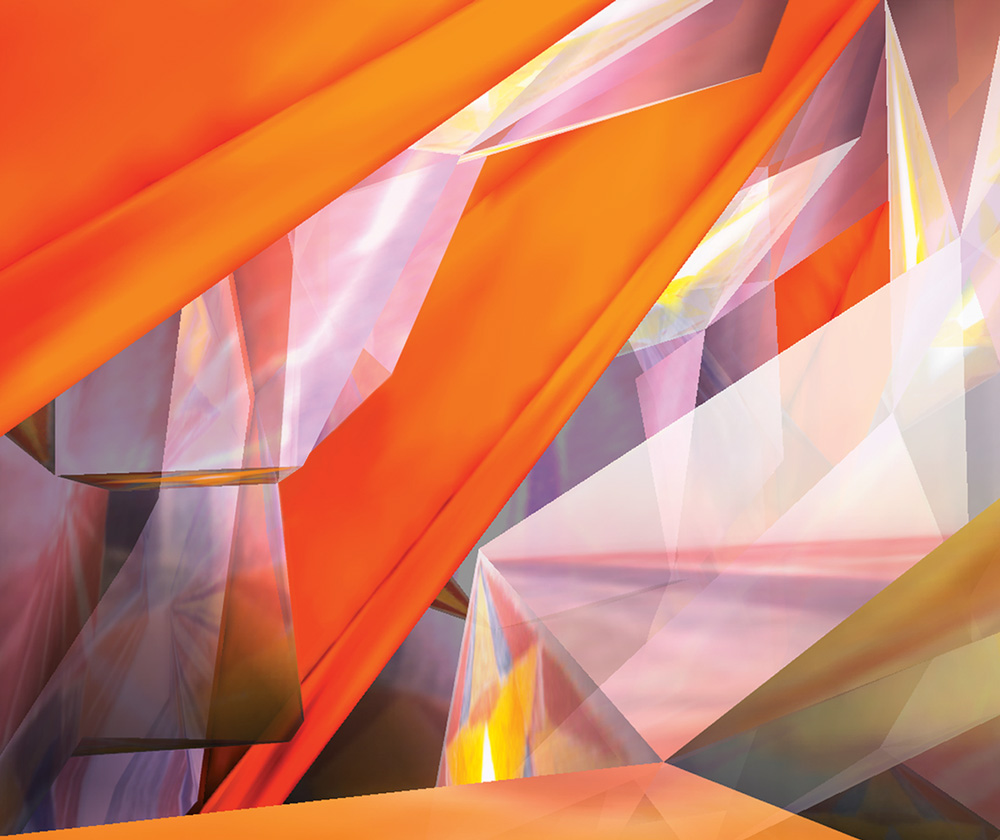

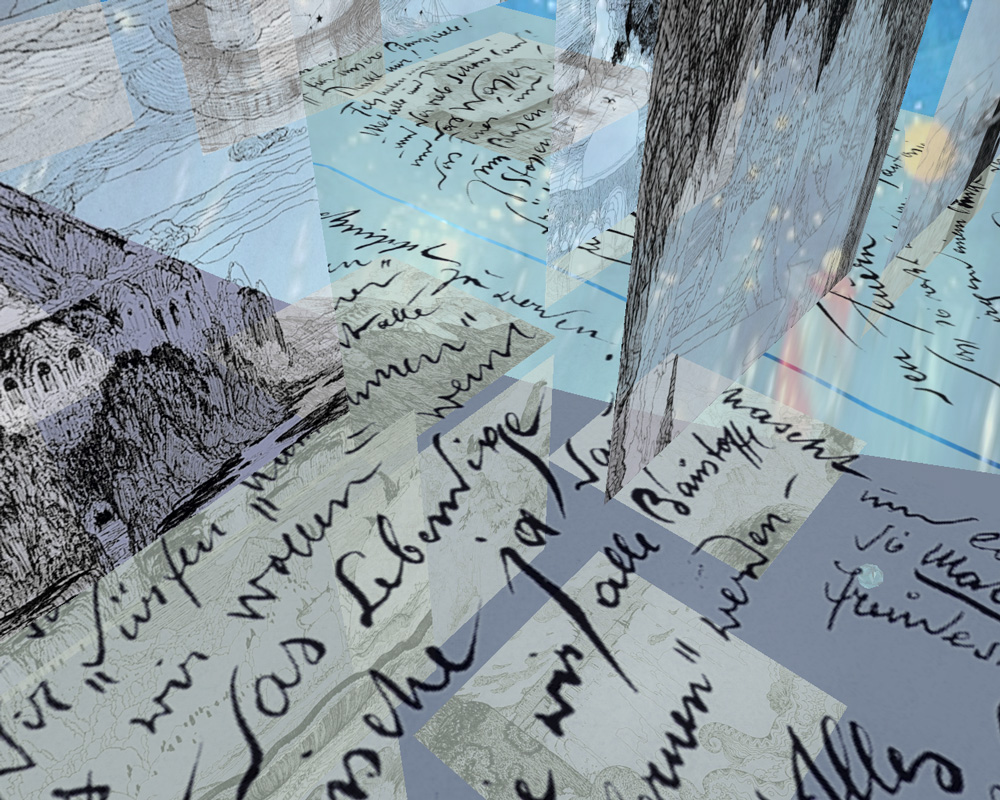

Eckermann‘s inspiration for n o w h e r e came from a secret society of modernist architects called The Crystal Chain (in German: Die Gläserne Kette) that formed in Berlin around 1920. They shared a utopian vision that viewed architecture as a vehicle for social change. In their writings, group members talked extensively about glass as a building material and it became emblematic of many of their ideals. Although the group itself was short-lived, its members ended up having significant impact on twentieth-century architecture.

Without this context, the work is still sensual and pleasurable. But knowing the background gives extra dimension and weight to the project. It is as though Eckermann is trying to manifest the ideals of The Crystal Chain in virtual space, perhaps creating a virtual architectural space that is a closer embodiment of those ideals than anything the original creators were able to accomplish during their own era.

This text was originally published in: Ninth Letter, 2006